Glenn

D Lowry, the Director of Museum of Modern Art in New York talks about

the impact of the Kochi Muziris Biennale on the international art

world and the artists making a mark

By

Shevlin Sebastian

The afternoon sun is blazing. So, it’s no surprise that even though Glenn D Lowry, the director of Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York is sitting in the shade of a shore-side restaurant, at Jew Town, he is wearing sunglasses. The reflection of the water can get a bit overwhelming, especially if you are not used to such tropical heat. But he is also smiling because he’s had a good time at the Kochi Muziris Biennale.

Asked how the art festival has evolved, Glenn says, “It is better organised and easier to navigate. There's more information for visitors. The mediators are doing a fantastic job of introducing artists and ideas to a public that might otherwise find it hard to access some of this.”

And the man who has travelled to all the major Biennales in the world several times over has some good news for the locals. “The Kochi Biennale has emerged very quickly as one of the most important biennials in the world,” he says. “If you think about it, it's only in its fourth edition and it has already become one of the key points in a network of major exhibitions like the Venice, Sydney, Sao Paulo and Sharjah Biennales. Anyone interested in understanding contemporary art has to come here.”

Not surprisingly, he is very excited by the Indian talent that he has seen. He opens his notebook, looks up and says, “I will mention a few names but these are just some among so many.”

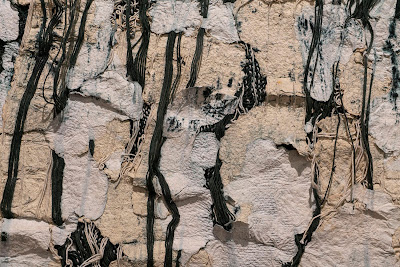

The names he mentions includes Bapi Das, Shubigi Rao, and Priya Ravish Mehra (1961-2018). “The work by Priya was particularly moving because one of the issues this Biennale deals with is the is the fragility of our planet, and the political, social, and economic ruptures that we are experiencing,” he says. “Priya’s work is all about suture, it's all about repair, it's all about healing damage, taking things that have been broken, ripped and torn and helping to knit them back together. It was extremely poetic and beautiful.”

At the Kochi edition, Glenn was very happy to see large numbers of people wandering around the various exhibits. “These are ordinary people who had brought along their children,” he says. “And that's an incredible achievement. India does not have as many museums of modern and contemporary art as she deserves to have. So the Biennale is playing an important role in providing access to top class art for people from all over India.”

MoMA in New York also provides access to top class art for all types of people. They have an astonishing 30 lakh visitors annually. But, interestingly, there are a few works that people see time and time again. These include Pablo Picasso’s ‘Les Demoiselles d'Avignon’, Vincent Van Gogh's ‘Starry Night’, Jackson Pollock’s ‘One: Number 31’, 1950’ and Henri Matisse's ‘Dance’.

Asked the reasons behind their popularity, Glenn says, “These are great works of art. Great works speak to different people across different times and places. Two, because of the media, they have become famous so people know about them. Third, often the story of the artist is more interesting. Van Gogh cut off a part of his left ear and later committed suicide. All of these things lead to curiosity. Artists are interesting people.”

Asked how they are different from ordinary people, Glenn says, “They are both like us and unlike us. Like us, they live in the real world. They have families, buy groceries, and vote in elections. Yet, at the same time, they have a certain kind of fearlessness. They are willing to talk about issues in ways that many of us, out of politeness or habit are afraid to talk about. And they are often able to talk about them in ways that help the rest of us see things in new and different ways. It’s a gift.”

But is this gift being hampered by the digital revolution where there are all types of tools to make art? “Yes, the digital revolution has allowed artists to use a new set of tools,” says Glenn. “But the works remain original and exciting. There are so many benefits: access to ideas and art has exploded. Now you can be in a village in Africa, a city in India or in the countryside in Canada and have access to the same information through the Internet. What it means is that artists can engage in conversations with each other more rapidly across more geographies than ever before.”

And keeping tab of all this is Glenn, who has been the director of MoMA for the past 24 years, a very long time to be at the top of one of the best museums in the world. But, he says, the reasons behind his success are simple. “I love what I do,” he says. “I am surrounded by extraordinarily talented curators, educators, conservators and archivists, so when I go to work every day I feel like a student learning from my colleagues and that makes it exciting. I love to look at art. I love to meet artists And so, for me every day is a new day.”

(The New Indian Express, Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kozhikode)