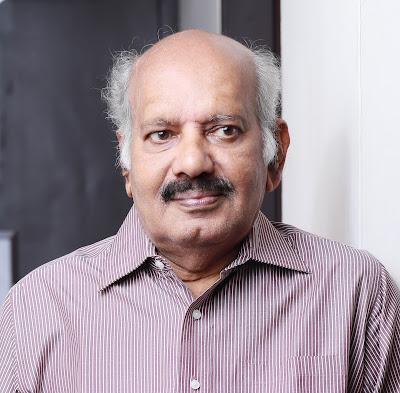

Malayalam

author Sethu’s first novel in English, ‘The Cuckoo’s Nest’ is

about a house for helpless girls run by a former nun

By

Shevlin Sebastian

One

of the surprises when you pick up ‘The Cuckoo’s Nest’ by author

Sethu, his first English novel, is the foreword. It is written by

none other than Sr. Jesme, who wrote the best-seling 'Amen', the life

of a nun in Kerala. But then it no longer becomes a surprise when you

realise one of the main characters is Madam Agatha, a former nun who

runs a home for troubled girls from all over the country.

But

Sethu clarifies that he had not read Sr. Jesme’s ‘Amen’ when he

wrote the book, which has been published by Niyogi Books. However, he

was aware of the troubles faced by her and other nuns in their daily

life because of the widespread coverage in the media. “Maybe, the

impact was unconscious,” he says. However, Sethu received a

compliment when Sr. Jesme called him up, after reading the novel and

said, “This is my story.”

In

the foreword Sr. Jesme writes, ‘Sethu has imbibed the nuances of a

woman’s mind who has left the convent life and is to be commended

for creating a character like Madam Agatha. She has transformed

herself from a religious entity into a secular personality.”

This

is true. Because, very early in the novel, Agatha says, “This is

not an orphanage run by the mothers or a madhom run by the swamis. I

had never asked you about your religion or caste, Neither did I

listen to your private prayers to find out your religion. Your

prayers are nothing but your attempt for a private communication with

the Almighty.”

She

also told the inmates that there should be no loud prayers or

chanting of bhajans of any community in the open hall. If one wanted

they could do so privately in their room, without disturbing the

peace of others. This would be a secular space and only those who

believe in secularism and tolerance should join.

And

Sethu had a specific reason to focus on these subjects. “It is to

highlight the situation the country is going through,” he says.

“This is my first socio-political novel.”

At

the ‘Cuckoo’s Nest’, there is a procession of girls from all

over India, like Sabeena, Parveen Singh, and Ranjini, who are

suffering from various psychological issues and running away to get

some mental peace.

Asked

why he attempted a novel in English, Sethu says, “It was an

adventure or you can call it a misadventure.”

What

is interesting to know is that Sethu studied in a Malayalam-medium

school in the village of Chendamangalam. “I did not learn English

properly,” he says. “What I know is acquired English. When I was

writing ‘The Cuckoo’s Nest’, over six months, I often consulted

the dictionary as well as a thesaurus.”

Many

of the characters are composites. What helped was that thanks to his

more than four-decade-long working career Sethu has worked in

Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Delhi, Andhra

Pradesh and Karnataka. And during his career, Sethu has met a wide

variety of people. “I am also comfortable with the languages and

cultures of these places,” says Sethu, who retired in 2005 as

chairman and managing director of the South Indian Bank.

The

reviews from readers have been positive. Says Moumita Roy: “The

story idea is unique and fresh. The character of Madam Agatha is well

researched. The scenario of the plot is relatable with current India.

The story has been narrated nicely. I enjoyed reading it.”

And

Sethu is also enjoying his 55th year as a writer. He has published 35

novels and short story collections. Among the many prizes he has won

is the Kendra Sahitya Akademi Award, the Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award

as well as the Vayalar Award. “It has been a long journey,” says

the 78-year-old with a smile.

(The

New Indian Express, Kochi and Thiruvananthapuram)